I always hear the same thing from many of my twentysomething clients: “I just need to find myself.” I wrote that in my own journal repeatedly, as if my identity were some fact waiting “out there” to be discovered. Like typing “who am I” into Google enough times might cause the answer to emerge, right alongside the atomic mass of boron and the circumference of the earth. But that isn't the way to find yourself.

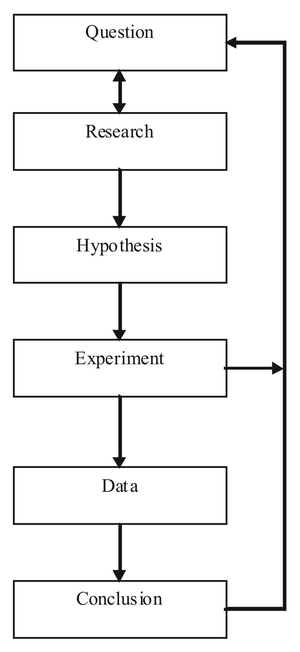

Instead, the best method to find yourself is to stop searching and start constructing. And I propose doing this like a proper scientist: By forming a theory. And revising it. Again and again.

Don't worry if you didn't make it beyond intro chem. The "science" you need to know you learned back in the first grade: the good ol’ scientific method.

Here's how I suggest using that little dandy to construct yourself - and a life you'll love:

1. To find yourself, start with a preliminary theory of who you are and what you want to accomplish.

Your "working theory" should be created based on your past experiences and reflections on those experiences. You’re looking to identify activities that put you in flow and overlap with the needs of the world in some way so that you can get paid to do them.

Example (drawn from my own life): I’m someone who wants to spend her days writing about and engaging with the field of psychology.

2. Create a hypothesis based on your theory.

This is a more specific idea about you and your work, usually in the form of a particular job that might be a good fit for you.

Example: I may find meaning and purpose in being a full-time freelance writer for textbook companies, focused on psychology.

3. Collect data.

In this stage, you live your hypothesis. In plain english, you go to work.

Example: I spend my days as a full-time freelance writer.

4. Analyze the data.

During this stage, you reflect upon your recent experiences and consider whether they are creating a sense of meaning, purpose and flow (i.e., true happiness), or whether something is missing.

Very important note: do not mix up the “collecting data” and “analyzing data” stages! All too often I see people constantly analyzing their experiences as they’re living them. Doing so tends to makes you not experience meaning, purpose and flow in your work for the mere reason that you’re trying so hard to identify whether you are in fact feeling those things.

Instead, commit to a time period for collecting data (e.g., I will try this job for one year before re-assessing) and THEN begin analyzing.

Example: About nine months into my year commitment to full-time freelance writing for textbook companies, I looked back and saw that the work was too isolating and solitary. I missed interacting with people and getting immediate feedback and reactions to things I shared. I enjoyed the deep engagement of writing, but it needed to be balanced with interpersonal activities in the future.

5. Revise the theory.

Take what you learned from your “experiment” and then change what you know about who you are and what you want to do. Or if the data analysis yields good results, by all means keep on keepin’ on!

Example: I’m someone who wants to spend her days writing about and engaging with the field of psychology, while having the opportunity to directly interact with people on a regular basis.

6. Create a new hypothesis.

Example: I’ll gain fulfillment from writing half-time and teaching psychology half-time. (This is indeed how I found my current work!)

And the process continues…

…hopefully for our whole lives. Being engaged in the experimental process of life is the good stuff, in and of itself. <Click to Tweet>

Once you embrace the scientific method of constructing yourself, life becomes one great experiment – one great adventure – that never grows stale.

The best part of this approach is that it takes the pressure off of finding the "right" path. If we think of life as an experiment, we free ourselves to try different alternatives, to not feel like we're wedded to a choice forever, and to not feel like we "failed" when a hypothesis ends up being unsupported by the data. In addition, this approach cuts analysis paralysis off at its knees, and also keeps concerned relatives off our backs. Who can argue with the scientific method, after all?

The Alternative

The people who are most dissatisfied with life are those who don’t even realize they’re constructing and refining a theory of self and life. They’re simply existing, going through the motions of making money and spending it, not sure what it’s all for, vaguely disappointed that life isn’t turning out the way they’d hoped.

They may want to know how to make life better, they might even be actively, incessantly asking the question, but if queried about where they are in the theory of their life, they'd have no idea. And they wouldn't care to figure it out.

Instead they keep typing searches into Google, waiting for the answer to their discontent to be revealed, not realizing that the best way to find yourself is to construct yourself, intentionally, systematically, and thoughtfully. <Click to Tweet>

Like any good scientist would do.

I want to hear from you: Where are you in constructing the theory of your self and your life?