You're screwed. That's the message millennials keep being sent. Such as in the New York Times' much-discussed article "Do Millennials Stand a Chance in the Real World?" which predicts that new graduates may feel economic pain for 15 to 20 years, even if fiscal prospects suddenly brighten. What's my take? This is good news. You heard me right: good news.

The economy stinks. And you'll be better for it.

It's Not the Economy, Stupid

Let's get this out of the way: the stretching of adolescence has not occurred because of the economy. The trend was noted during the economically expansive 90s and the term "emerging adulthood" was coined in 2000. Furthermore, features of emerging adulthood - identity exploration, instability, self-focus, feeling in-between and having a sense of possibilities - are observed in people from all economic backgrounds.

Since prolonged youth is a psychological phenomenon, not an economic one, we need to stop hiding behind the bad economy as the reason we're living with our parents and putting off figuring out our lives. We were doing that when the economy was plum and we'll be doing it when the economy rosies back up. So economic forecasts? They simply don't mean much to me. Tell me what's going to happen psychologically instead.

You'll Never Have to Downsize

You might look all green-eyed at me and my 90s peers who graduated with jobs in hand. Not so fast.

One of the more painful things a person can be asked to do is to downsize. Following the concept of the hedonic treadmill that we discussed in our "Chase Happiness" class, we quickly adapt to whatever pleasures surround us and then come to expect those pleasures as a baseline for our contentment. (And, indeed, to desire even more.)

Furthermore, we overvalue things we own; we might have thought a mug was worth $2 before it was ours, but once we own it, it's worth $10 in our eyes. This is called the endowment effect and it helps explain why we're loathe to give things up.

Many people who graduated in the past two decades accepted lucrative post-college gigs while saying, "I don't plan to do this forever. In truth, I don't like finance/insurance/dot-coms, I love _______, but I'll go back to that in a couple of years. I'll just earn a little money, and then I'll go to grad school/join AmeriCorps/become a teacher/take a severe and debilitating pay cut."

HA! As if.

Instead they got stuck in that job they never liked for years on end. Miserable, they wandered around saying they still wanted to go after what they love. But they didn't know how. The money, the lifestyle, the plushness, it was all too good to give up. Until they were forced out by layoffs. Now they're too busy desperately clawing to get back what they lost to think about what they used to want.

You Millennials will never have such problems.

You Can Make Use of Underemployment

Millennials tend to be unemployed or underemployed. This is nothing to sneeze at. As Meg Jay says in her book The Defining Decade, "Those who are underemployed for as little as nine months tend to be more depressed and less motivated than their peers-than even their unemployed peers." And unemployment in the twenties is associated with "heavy drinking and depression in middle age even after becoming regularly employed."

So, yes, we're dealing with serious stuff here.

That said, unemployment and underemployment can be prime opportunities to forge your identity - if you embrace them as such. Think of it like a snow day*. Remember when that happened as a child? You woke up and your mom announced you didn't have to go to school and you could stay home and do whatever you wanted all day long? How did you react? Did you let yourself get paralyzed by the crush of options that then lay before you, or get depressed over the lack of options that were within the confines of your home? Or you did you instead seize it as an amazing opportunity to do everything you always dreamed of doing when you were sitting in school, bored to death?

So too with unemployment or underemployment. You can lament what's not happening in your life, or you can use the cognitive and/or temporal space to plot out what you want to be happening in your life. You can choose to sit in the uncomfortable space of an identity crisis (which isn't a bad thing), make active decisions about what you can do to work toward the identity you decide you want, and start to make incremental steps in that direction. You don't always need a job to help you gain identity capital - volunteerism, attending adult education classes, networking, or honing skill sets on your own time can do that just as well.

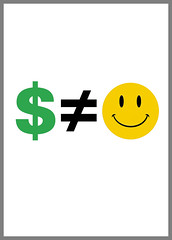

You Don't Need Money to Find Fulfillment

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we know from our class "Money and Happiness" that beyond about $50,000, money doesn't equate with fulfillment. Granted, even that salary is hard for millennials to find. This is a real issue, which plenty of others have taken up. While we're perseverating on the ugly economical outlook for millennials, though, we're completely ignoring the psychological outlook. I'd love to see data about the psychological outcomes for various generations; are people from the 1990s cohort actually better off psychologically compared to those who joined the work force during the recession of the 1980s?

Given what we know about the paths to happiness, I can't imagine the 90s graduates are. Happiness comes from finding work that you find meaningful and that puts you in a state of focused challenge called "flow" on a regular basis. It does not come from material pleasures.

Furthermore, materialism has been linked to problems with intimacy, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem, as Tim Kasser discusses in his book The High Price of Materialism.

Finally, when we have little, we tend to be more grateful for that which we do have. In many studies, such gratitude has been linked to psychological well-being. Thus when the New York Times notes that millennials are developing their "own Depression-era fixation with money" I think, is that such a bad thing? Even the Wall Street Journal admits that economic downturns result in psychological boosts, including less complaining. "In many quarters, we're seeing a return to Depression-era stoicism and an appreciation of simpler things," writes WSJ's Jeffrey Zaslow.

Final Thoughts

So remind me again why millennials don't "stand a chance"? Because their economic portfolios will take a hit for the foreseeable future? On the contrary, when it comes to psychological well being, identity formation, and the building of a genuine life, I think millennials stand a better chance than young people have in decades.

*Thanks to agent Sorche Fairbank for the snow day metaphor. She used this at a writers' conference I attended, as a way for writers to embrace the economic downturn.

The bad economy is not to blame for our desire to avoid adulthood. (Photo credit: Mathew Knott)

A tiny apartment is fine. When you've never had anything better. (Photo credit: nekosoft)

With a job like this, there's plenty of cognitive space to do some serious thinking. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

We all know this to be true. So why do we focus solely on the economic details? (Photo credit: agitprop)