Q: What's your take on laziness? Is it an epidemic or what? I once had a discussion with my friend about how we are less productive when we are less busy, if that makes sense. For example, when we have a full schedule with deadlines, requests to fulfill, appointments, assignments, etc., we find ways to make it all happen. Then, when we finally get "free time" to accomplish all the things we've been wanting to do for ourselves, like go to yoga, workout, clean, blog, etc., we don't end up doing much of those things at all! There is no one but ourselves to hold us accountable for those things, which makes it all the more difficult to get it done with any urgency. - Isabel Gomez, @izzygomez A: You're definitely onto something with your observation, Isabel. You should see my low productivity in the summertime when I'm not teaching - I often fail to even make it to the grocery store!

Why would less time make us more productive? Because it stresses us out - in a good way.

We need good stress (eustress) to perform optimally, according to the Yerkes-Dodson law. Not enough stress and we're like sacks of potatoes on the couch. Too much and we're a bundle of ulcer symptoms.

But I think there's more to the "laziness epidemic" than a lack of stress. In fact, it's just the opposite. It all comes down to an improper understanding our "Optimal Time Crunch Zone." (It's not as scary as it sounds - promise!)

Get Your Time Crunch On

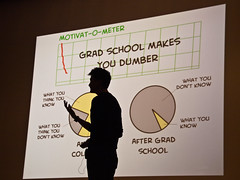

Before we dig into the laziness issue, let's get clear on our Optimal Time Crunch Zone by extending the Yerkes-Dodson law to "Time Crunch Status," as shown in this image I created.

It demonstrates that we need to be somewhat time crunched to be optimally productive.

It demonstrates that we need to be somewhat time crunched to be optimally productive.

Too much time on our hands is a recipe for getting nothing done - and too little time is exactly the same!

The big question is, how much time crunch is "too much" and how much is "not enough"?

How to Find Your Optimal Time Crunch Zone

What feels like a ton of free time to me (a whole HOUR today?!?) may feel like nothing to you - or vice versa. So we have to do some trial-and-error to find what amount of free time works best for each of us.

We can do that totally randomly. Or, if you're a dork like me, you can be a bit more strategic about the process, say, like this:

- Identify your current Time Crunch Status.

- Signs of low Time Crunch Status = not bothering to do the things you want to be doing (e.g., the blogging, going to yoga and cleaning that you mention, Isabel), fatigue, lack of motivation

- Signs of high Time Crunch Status = irritability, forgetfulness, exhaustion, missing deadlines, physical ailments like headaches and digestive issues (all sorts of fun!)

- Signs of being in the Optimal Time Crunch Zone = You aren't worrying about this issue at all! Things are just flowing.

- Jot down your Time Crunch Status AND how many hours a day, on average, you currently have "free" (i.e., the hours you get to fully determine what you're doing).

- Put these notes somewhere you can refer back to them months - or even years - later.

- If you're not currently in your Optimal Time Crunch Zone, tinker with your Time Crunch Status.

- For low Time Crunch Status: try adding a bit more requirements to your day, such as by taking on a volunteer position.

- Notice I said "adding a BIT more" - I've seen many students take this too far too fast, passing right by the Optimal Time Crunch Zone into danger territory. I must admit I did this at the start of my first few semesters of college: workload felt so light during the first two or three weeks that I signed up for a ton of activities so that I didn't have so much free time. I'm sure you can imagine what happened to me by midterms. Ugly.

- For high Time Crunch Status: Uh, yea. This one is difficult and I'm no master here. In theory, we should list everything we have on our plate, prioritize that list based on what each brings into our lives (both extrinsically and intrinsically), and then pare off the bottom items one by one until we hit our Optimal Time Crunch Zone. In practice...uh, yea.

- Continue to tweak and keep track until you see your personal pattern emerging. Then you'll know what's too little free time for you - and how many hours is too much!

- In my experience, this "need for time crunch" remains remarkably stable over time. When I think to my friends from high school, I can think of some people who LOVE to be crunched to an extent I couldn't stand, and others who wouldn't want to endure my pace. Although just about everything else about us has changed in 20 years (good bye frizzy hair!), our individual Optimal Time Crunch Zones haven't moved much at all.

The Scoop on "Laziness"

To return to your initial question, "What's your take on laziness? Is it an epidemic?" I'll start by saying that I don't believe "laziness" is an innate characteristic, per se.

Although Peter from Office Space claims he'd "do nothing" if he never had to work again, I don't believe him. Nobody is that inherently "lazy." All humans have stimulus motives, which make us feel horrendous if we're not stimulated "enough."

Instead, I believe "laziness" arises from a lack of understanding of our Optimal Time Crunch Zone.

And, yes, it's an epidemic. We're a culture so obsessed with being busy, we experience tons of burnout that LOOKS like laziness.

In other words, we operate so far above our Optimal Time Crunch Zone for so long that when we finally get a moment to chill out, our bodies scream for us to STOP. Completely! Then we berate ourselves for not getting anything done.

Pretty ridiculous.

Once we get clear on our Optimal Time Crunch Zone, however, we know precisely how much we need on our plates to feel productive and energized. THEN we can work on breaking the "overly busy/overly tired" cycle by respecting our needs.

The "respect" part is what I'm still very much working on. My strategy? Intentionally spending time around people who operate in their Optimal Time Crunch Zone on a regular basis.

That's the best we can do, I think: become aware of our patterns, look for healthy models to help us break those patterns, and forgive ourselves when we (inevitably) slip up.

One hour at a time.

Thanks for the great question!

What's your take on time crunch and "laziness"? How do you find the healthy balance between being stressed and being bored?

Do you have a question about work, careers, finding your path in your twenties, identity, or what you should eat for dinner? Wait, not that last one. But if you have any other questions, pop them my way @WorkingSelf or Rebecca@workingself.com. I may not know the answer, but I'll grapple around in my experiences and research to help us puzzle through it together. If your Q is published, I'll send you a free e-coaching session on values!